Untitled (Partition), 35mm slide on ADOX SCALA 160, 2018.

‘Untitled (Partition)’ Lecture

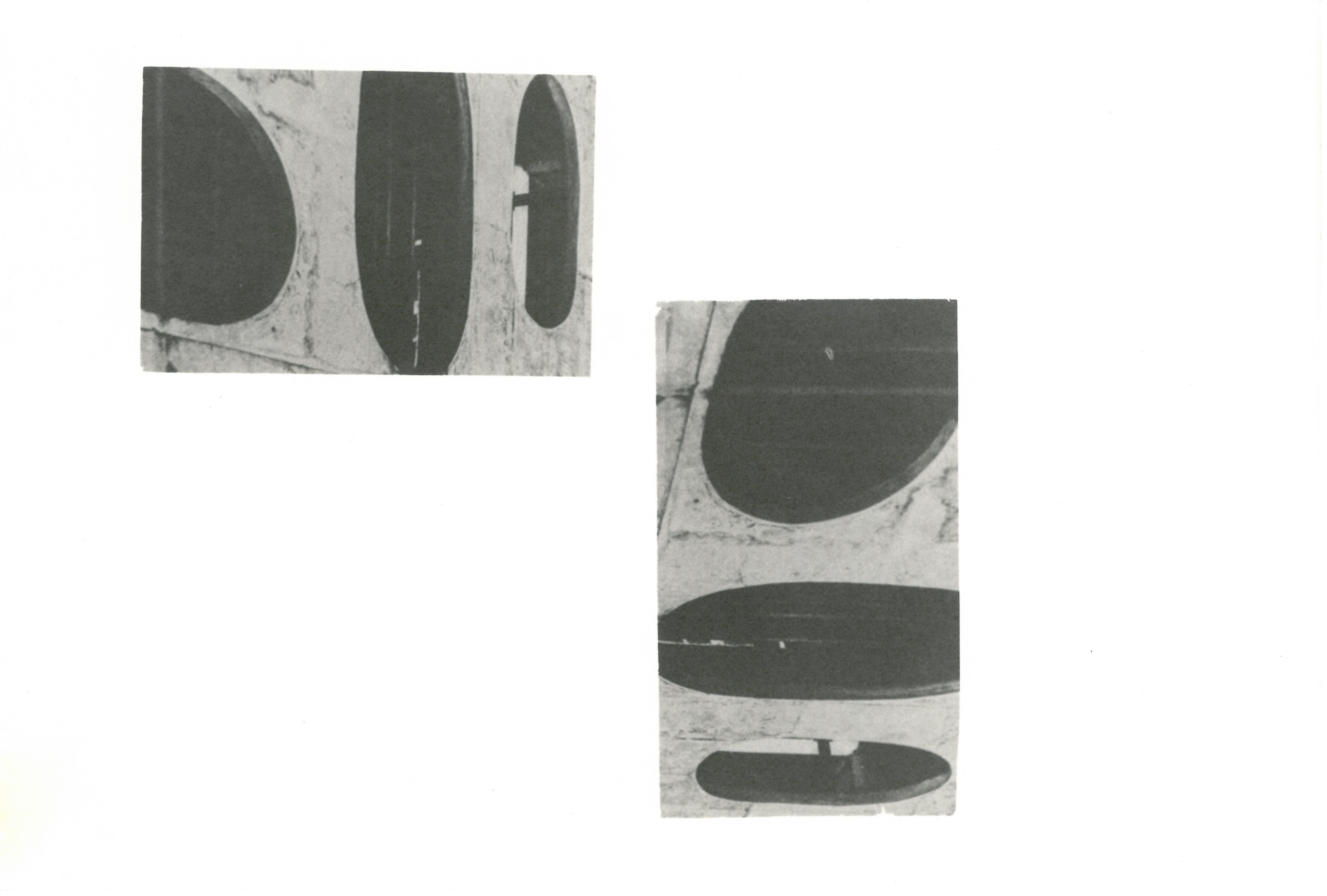

Slide 1: Pure form

Slide 2: de-populated space

Slide 3: Timeless locations

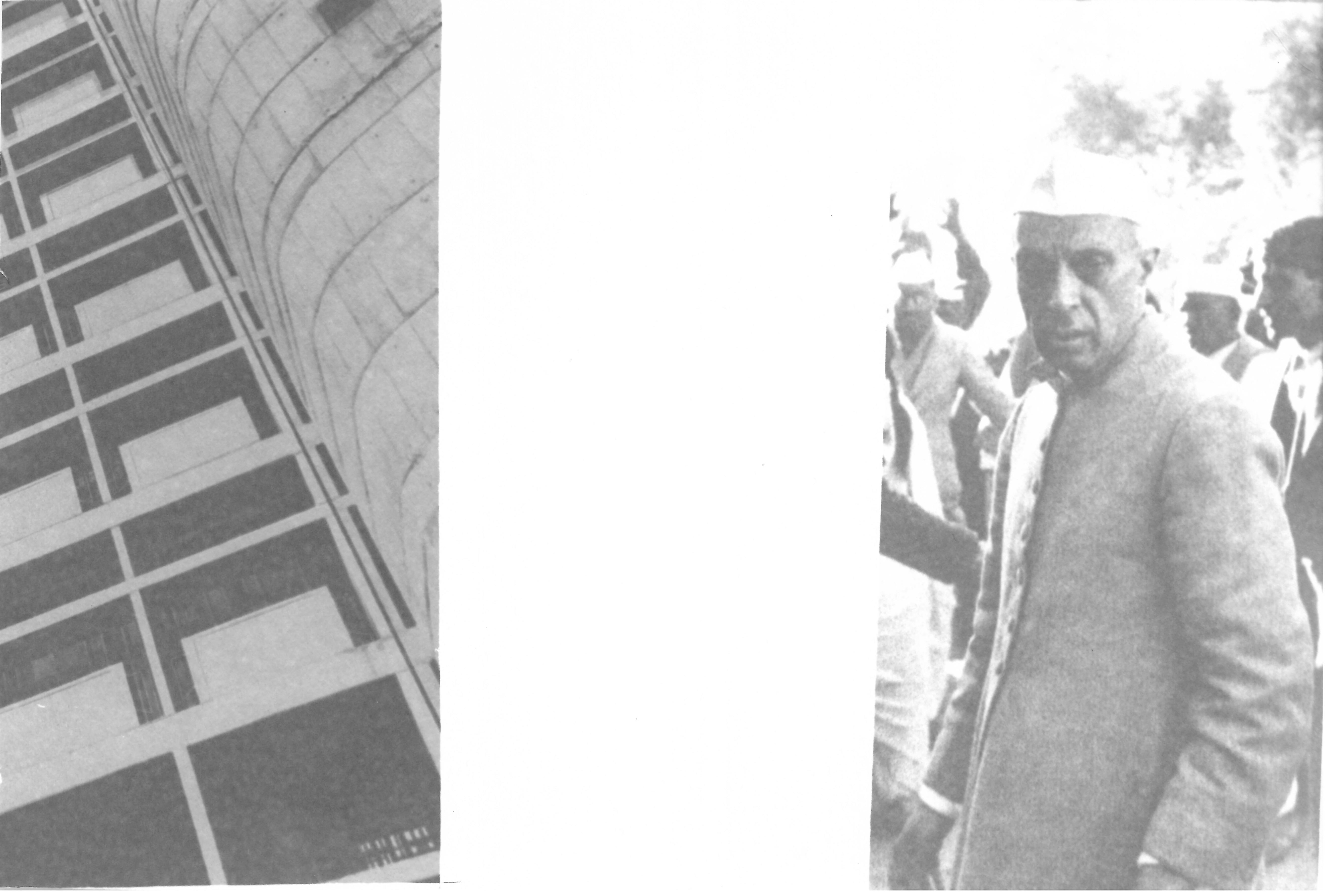

Slide 4: Gridded facades

Slide 5: Vistas through curvilinear frames

Slide 6: Triangles imposed upon the horizon.

Slide 7: Reproduced and rearranged.

Slide 8: Order achieved.

Slide 9: Relationships established, in abstraction from the landscape.

Slide 10: ‘The architecture photographer’s vision must be disciplined.’

Slide 11: These are Herve’s words.

Slide 12: What was he looking for in Le Corbusier’s buildings?

Slide 13: … and what did it mean to them?

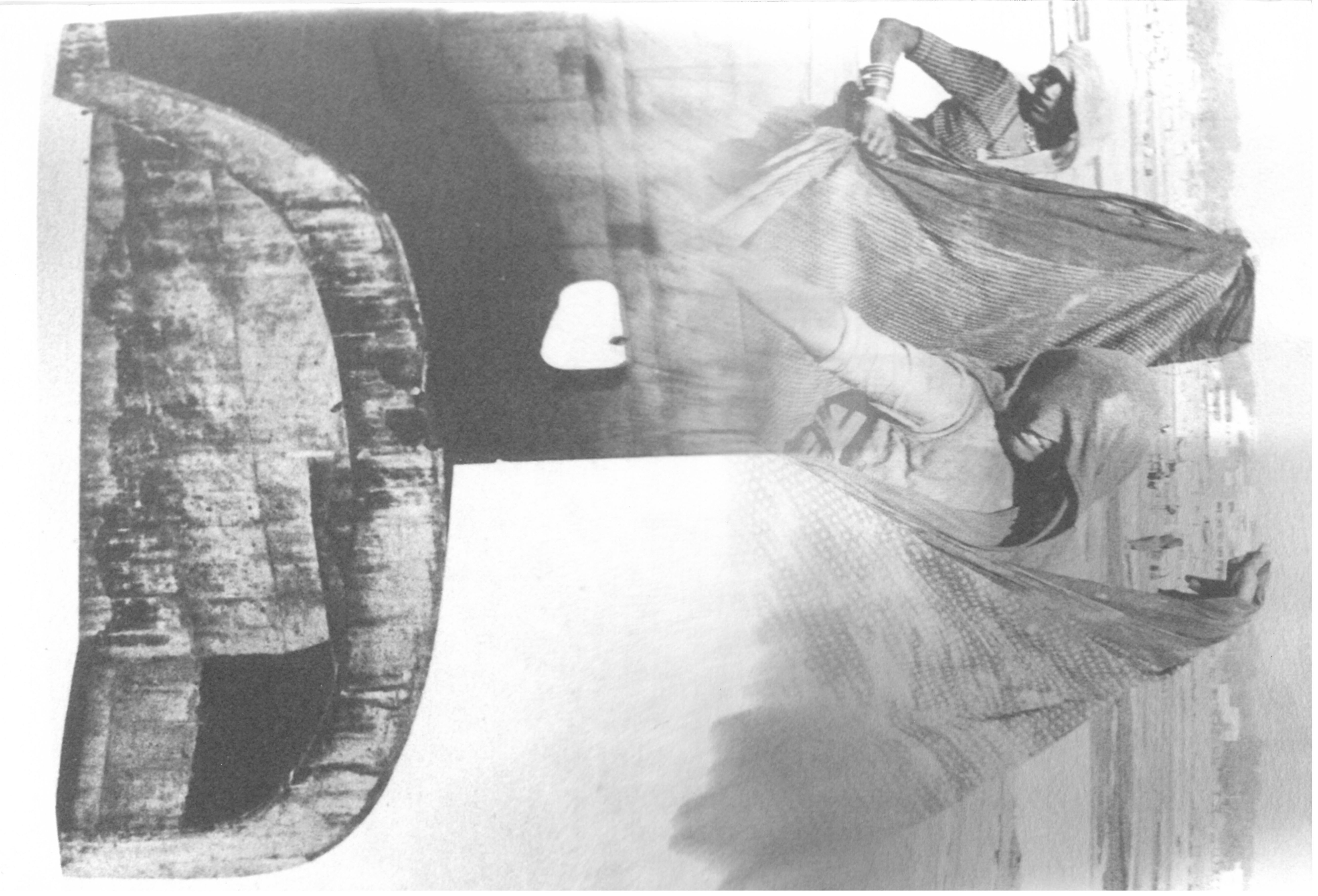

Slide 14: … and how did Herve’s vision coincide with Nehru’s?

Slide 15: Herve’s photographs accentuate the aesthetic dimension of Le Corbusier’s designs. His images articulate buildings as abstract geometries, flooded with light.

Slide 16: Architectural form can function as monumental statement.

Slide 17: Architectural form can function as auratic gesture

Slide 18: Or, architectural form can function as utopian vision. Can it help to re-create regional identities?

Slide 19: Or, do such autonomous architectural forms impose placelessness? The outcome of projects, such as Chandigarh, rests as much in their social history as in their design. The same can be said of Herve’s photographs?

***********

Slide 20: The Great Partition imposed borders upon India.

Slide 21: … and necessity made Chandigarh the capital of Punjab. A European architect designed the plan.

Slide 22: Working out who you are once the colonisers leave is a difficult problem.

Slide 23: Especially, when modernisation means borrowing from colonial nations. If you accept modernism is a European invention.

Slide 24: Consider the issue alternately. An architectural project can only succeed if appropriately aligned with a social project. If we follow this line of thinking, The Third World project is perhaps the context in which International Modernism could flourish.

Slide 25: But what then of the region’s own history and culture … and all of the upheaval? Where is that in Le Corbusier’s plan?

***********

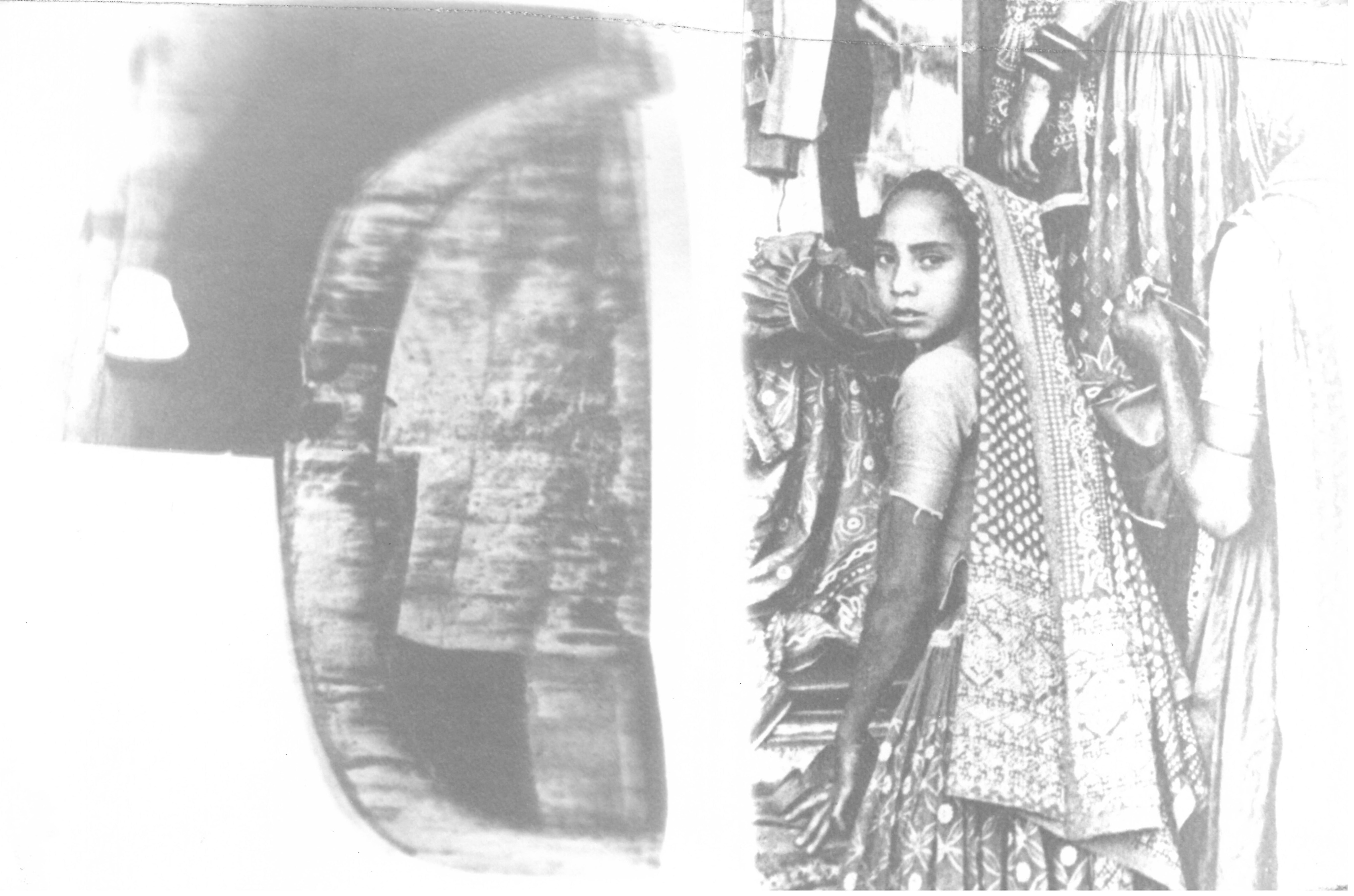

Slide 26: The American Margaret Burke-White and Frenchman Henri Cartier-Bresson, made key canonical documentation of The Great Partition. Burke-White’s and Cartier Bresson’s images now provide a lens through which we view the events of 1947-48. The issue of colonial legacy is also relevant to documentary photography.

Slide 27: When we align Burke-White’s and Cartier Bresson’s images with Herve’s, we see contrasting applications of photography. In one, we see a universalising template for life, conveyed in abstract units of concrete. In the other, we see the everyday unfold, as seen within the viewfinder.

Slide 28: Each exploits photography’s contradictory testimony, based in the scientific technicality of the apparatus, and the individual vision of the photographer. Each photograph asserts a truth claim - ‘The image shows what’s there’. The assumption burns into the optic nerve of the spectator.

Slide 29: To view photography through these assumptions produces a blindness to contextual processes of visual communication. Images do not represent; they act, moving information and affect from one place to another. To address the questions posed by cities, such as Chandigarh, we must first sever the link between documentary photographs and assumptions of unequivocal testimony.

Slide 30: Testimony is something that we must actively negotiate, so we can navigate the relationship between what images show and their presentation in context.

Slide 31: Herve’s images make sense in terms of the absence of daily life, which we know through the documentary work of Burke-White and Cartier Bresson. The social construction of each photographer’s work underpins its mythic status. This is how the one can dwell in abstraction and the other in the grain of life.

Slide 32: We should view these images as tools through which we can re-evaluate the legacies of colonisation.